- Home

Welcome !

Welcome to john houghton's home page for his biology courses. This site is designed as a hub for curating and sharing lectures, course syllabi, assignments, and links to relevant resources. Use the menu bar at the top of the screen to navigate through the site.

(Please note: this page is currently under construction.)

- BIOL 2107

Fall '23 CRN86772

Lectures: (1)

- Courses

BIOL 2107 Principles of Biology I

- Resources

General Resources

Gene linkage and the role of the sex chromosome:

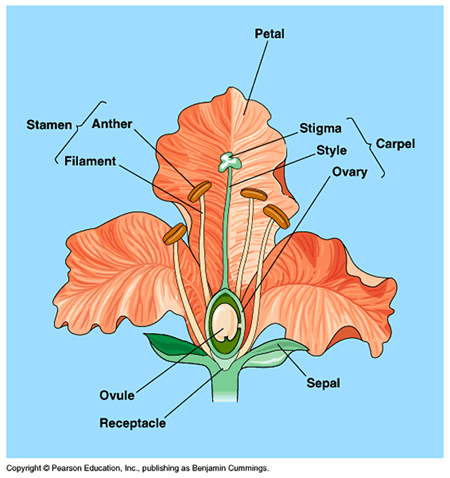

Mendel did all his analyses with plants, which -like many other plants- exhibit BOTH male and female reproductive structures in the same adult plant (termed monoecious, or "all in one house").

What about animals and plants that have individuals which are either one or the other sex (termed dioecious, or having “two houses”).

In most dioecious organisms, term that is normally used for plans, but can apply to any organism, where the sex of the organism is determined by differences in the presence/absence of a set of chromosomes, or the presence/absence of discrete chromosomes.

In honeybees, eggs are either fertilized -and become diploid females- or they are not fertilized -and become haploid males, drones.

In Mammals, such as humans...

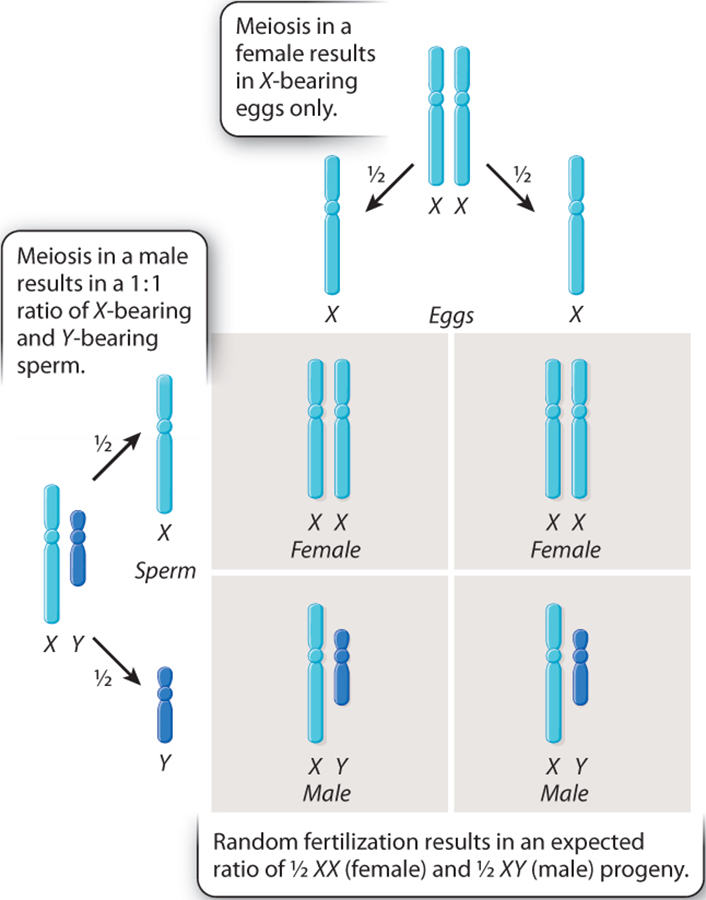

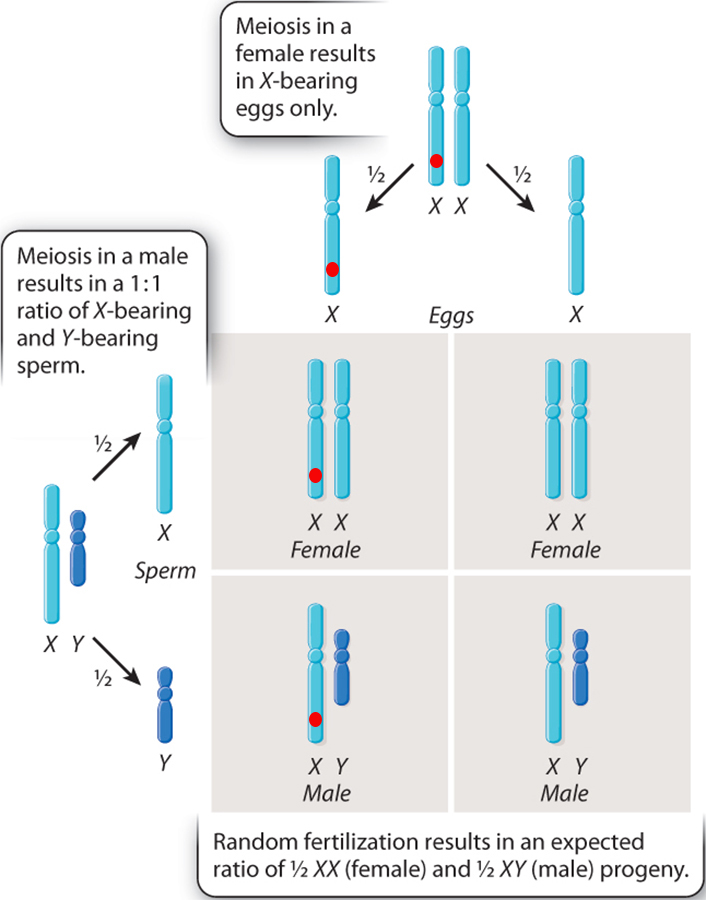

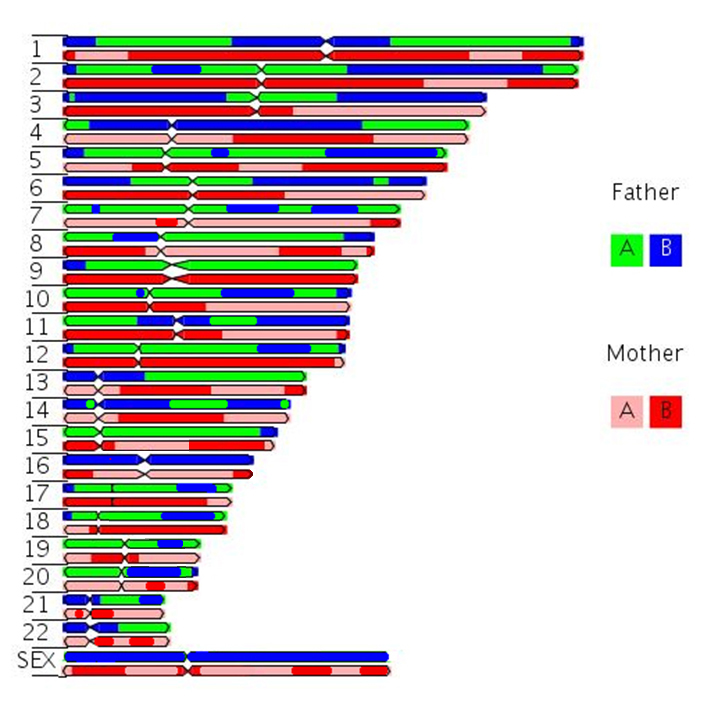

Humans have different sex chromosomes, X and Y. Males have X and Y; females have X and X.

Again, the sex of the offspring is also determined by the sperm.

If a sperm with an X chromosome reaches the egg, the resulting offspring will be female (XX). If a sperm with a Y chromosome reaches the egg, the resulting offspring will be male (XY).

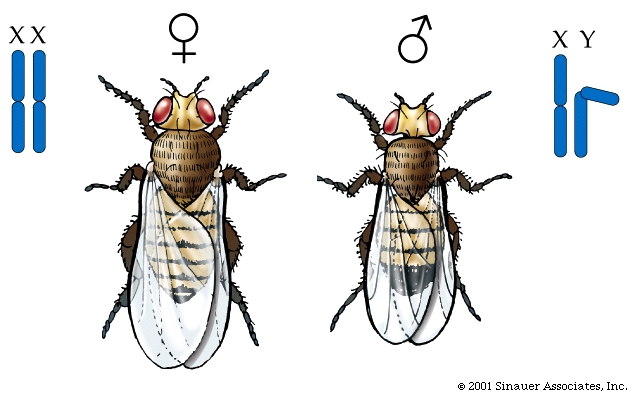

In the Fruit fly (or Drosophila melanogaster) chromosomes also have distinct X and Y chromosomes, wherein the male is XY and the female is XX. As a consequence, like humans, the male fruit flies are said to have a set of paired "autosomal" chromosomes and then one X and one Y chromosomal. They are, therefore said to be hemizigous.

In mammals the X and Y chromosomes have different functions

The gene that determines maleness in mammals was identified by studying people and animals with chromosomal ploidy abherations... as, unlike most autosomal ploidy variations, mammals can handle some varaiation in the numbers of X and Y chromosomes.The gene was named SRY (for Sex-determining Region on the Y chromosome).

The SRY gene codes for a functional protein (TDF or Testis Determining Factor) involved in primary sex determination.

A gene on the X chromosome called DAX1 produces an "anti-testis" factor. The SRY gene product in a male inhibits the gene DAX1, and consequently no "male-specific" inhibitor is made.

Secondary sexual traits like breast development, body hair, and voice are also influenced by hormonal levels of key sex hormones -such as testosterone and oestrogen.

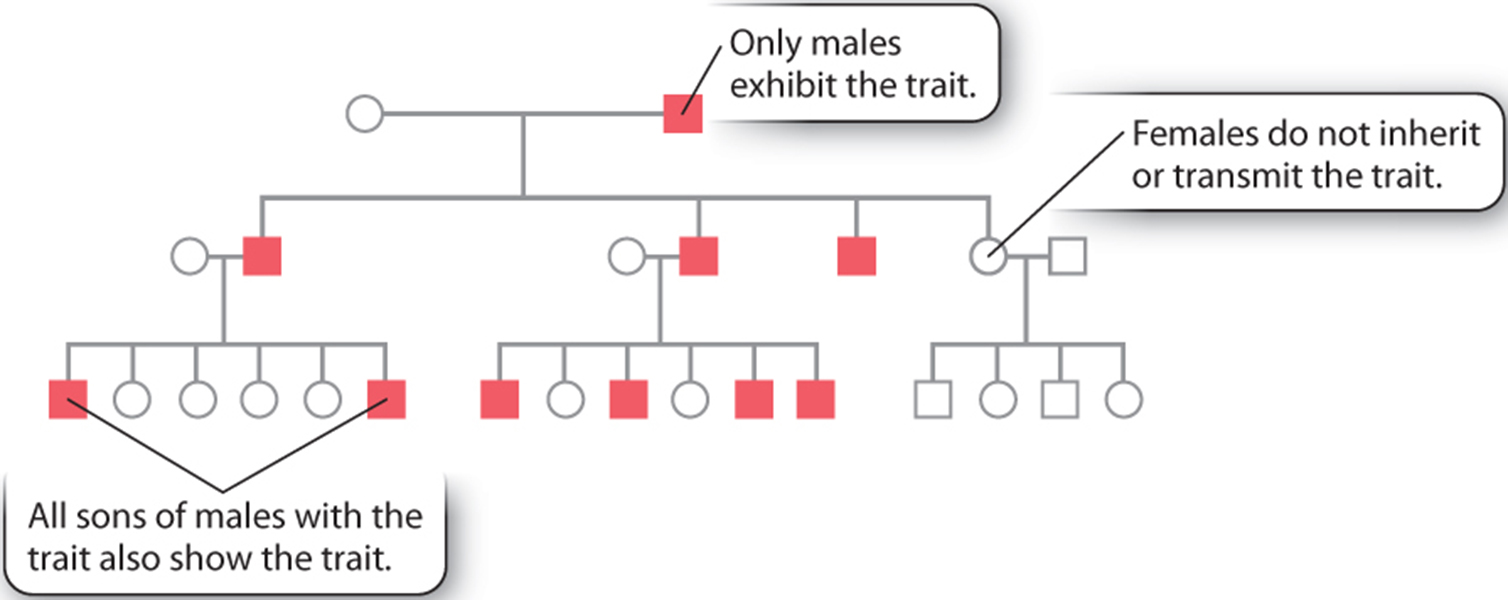

The presence of Sex chromosomes allows for a special type of genetic inheritance to be analyzed..... sex-linked inheritance. In essence, while a female can be heterozygous for a particular gene that is present on the X chromosome, her male offspring will be hemizygous for that particular trait.

if the allele on the X chromosome is recessive, whil it may be "masked" in a heterozgous female it will always show through in her male offspring.

Consequently it is relatively easy to trace an X-linked trait that has an overt phenotype. One such trait, which has become somewhat infamous among genticists (especially in England because there are lots of data available with respect to lineage and heritable traits) is the passage of Haemophaelia within the English royal family.

On a less morbid note about another type of X-linked trait Red, Green Colour blindness.... true story!

While the X and Y chromosomes normally behave according to the laws of meiotic cell division (and thus according to Mendelian genetics) the ability to "visualize" the presence of each of the alleles that is located on either of the X-chromosomes of a mother (by observing the different phenotypes) challenge the ubiquity of Mendel's 2nd law, or in other words...

Mendel's 2nd Law DOES NOT ALWAYS APPLY to X or Y -linked chromosomal inheritance!!!

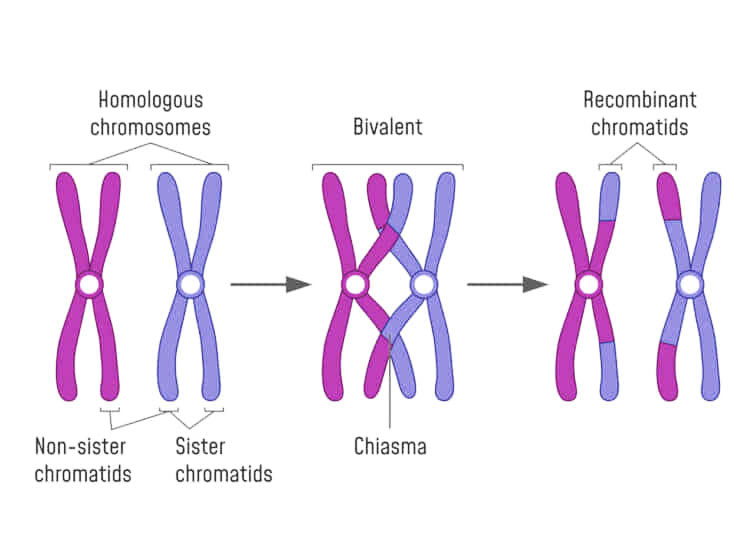

Remember, that ......to equate Mendel with meiosis we had to invoke the role of "chiasmata" an their occurance between two gene loci on adjacent chromatids in paired, "bivalent" chromosomes during prophase I of meiosis.

We now know that this CANNOT occur for X and Y chromosome... OK, but what about ALL the genes on the other autosomal chromosomes.

I glibbly stated that, if the probability of a single chiasma forming between two genes is "one" (i.e. a certainty), then the assortment of alleles would, in essence, be the same as if they were on separate chromosomes (i.e. random).

But, what happens if there are no chiasmata formations?

Then the genes on the same chromosome cannot assort randomly, which would be in marked contrast to Mendelian expectations.

However, this phenomenon can and does happen.

Such aberrations were first hypothesized to exist by Bateson and Punnett, who observed some curious "associations" of heritable traits. However, it was really verified by an American geneticist, Morgan (1909) who was working on chromosomally-linked genes that resided on the X chromosome of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. He was able to confirm that crossing over didn't ALWAYS occur in ALL X chromosomal traits during Meiosis in the Female Fruit Fly...

So, what happens if there are NO CHIASMATA formations between homologsous chromosomes once they come together...in what phase of Meiosis?

Morgan explained this apparant anomally by proposing that the two loci were present and "linked" on the same chromosome...

Thomas Morgan (1909) while working on chromosomally-linked genes that resided on the X chromosome of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster also was able to demonstrate and confirm that crossing over didn't ALWAYS occur in X chromosomal traits, even in females... if the gene pairs were SO close together that crossing over COULD NOT PHYSICALLY HAPPEN.

While not common, he also confirmed that this "linkage" phenomenon can also happen -even with some genes on the autosomal chromosomes.

So, now we have analyzed two "variations" from the "predictable" Mendelian-type of inheritance,

(a) variations that arise as a consequence of "extensions" to Mendelian genetics, where the function of the genes in question may interact to give different F2 phenotypes.

(b) variations that arise because of "chromosomal linkage" (thus defying Mendel's Second law).

So, Mendel was not always right for a number of reasons... but this type of non-Mendelian Genetics has additional ramifications

Is there a female equivalent to this purely male based pattern of inheritance?

Well yes, but it is not sex-linked on the Y chromosome

This form of inheritance defines a THIRD form of non-Mendelian genetics.....

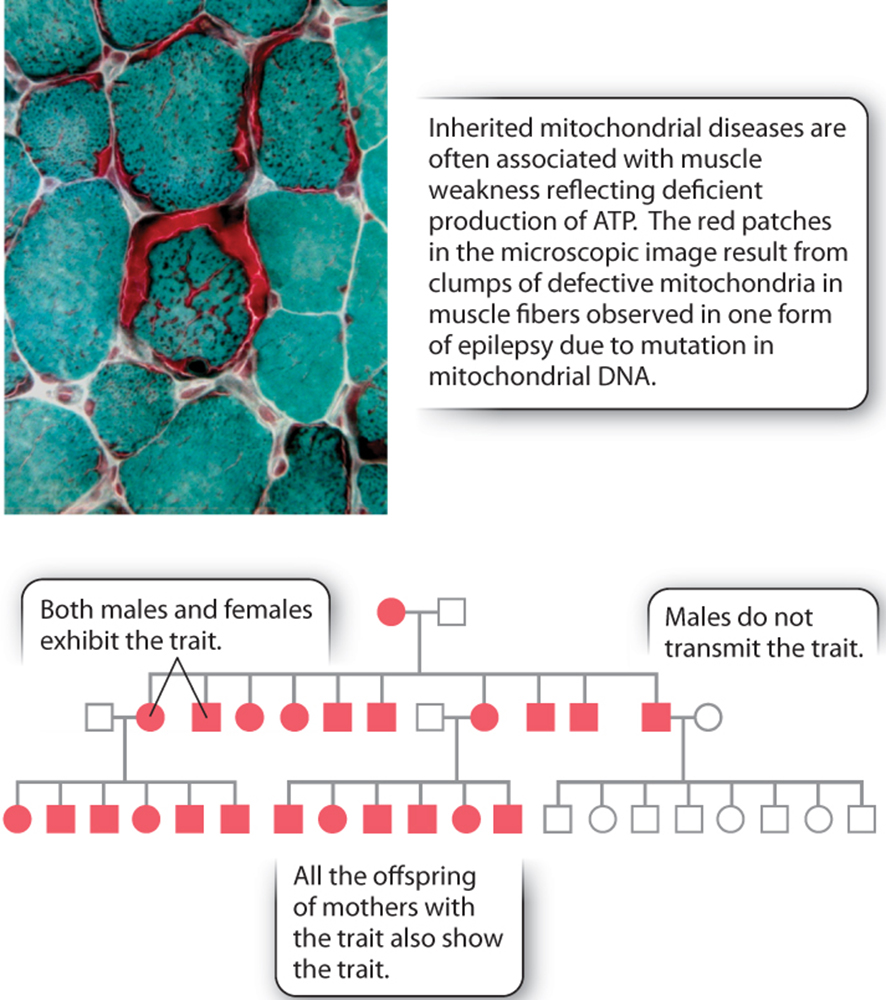

(c) Cytoplasmic / Maternal Inheritance

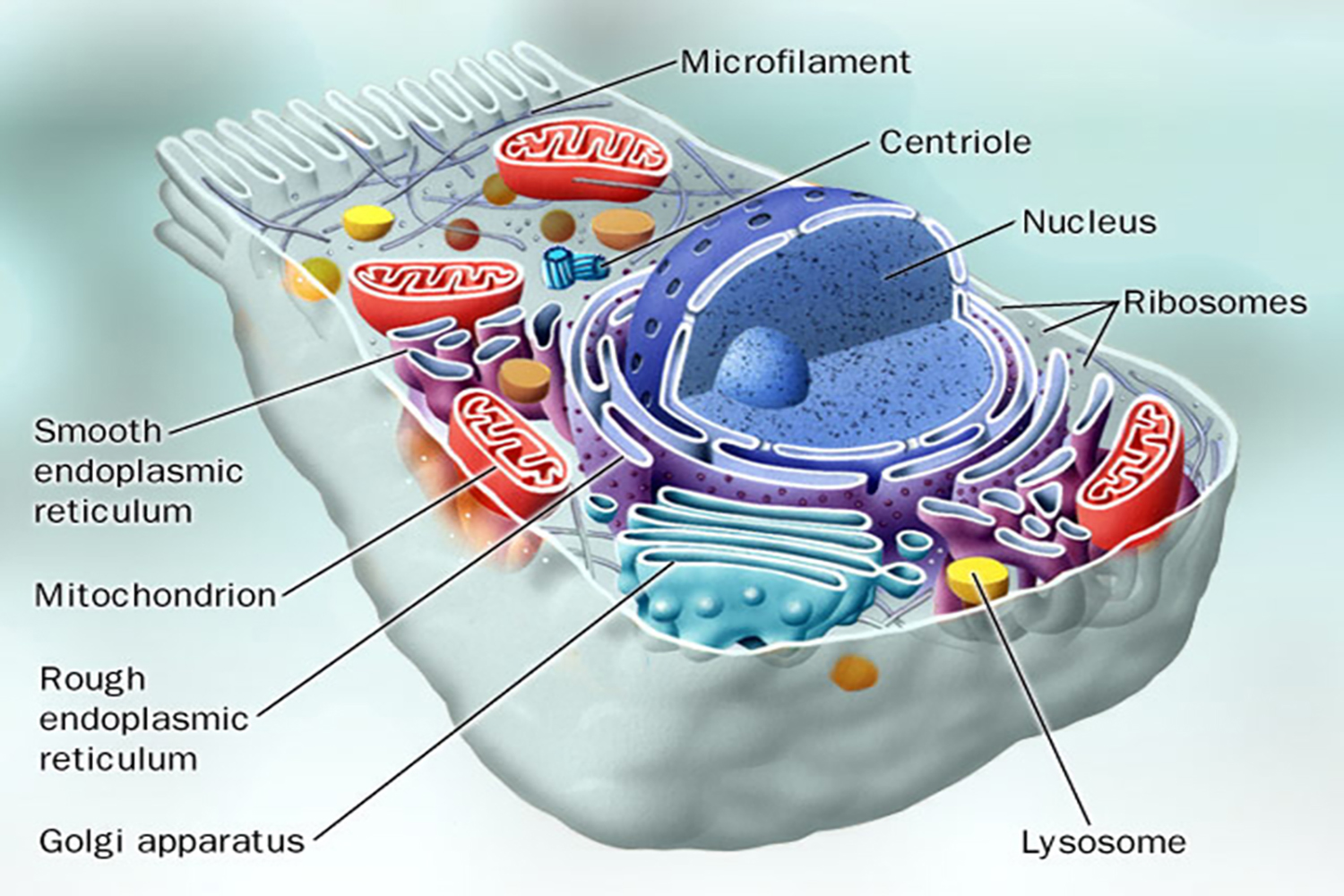

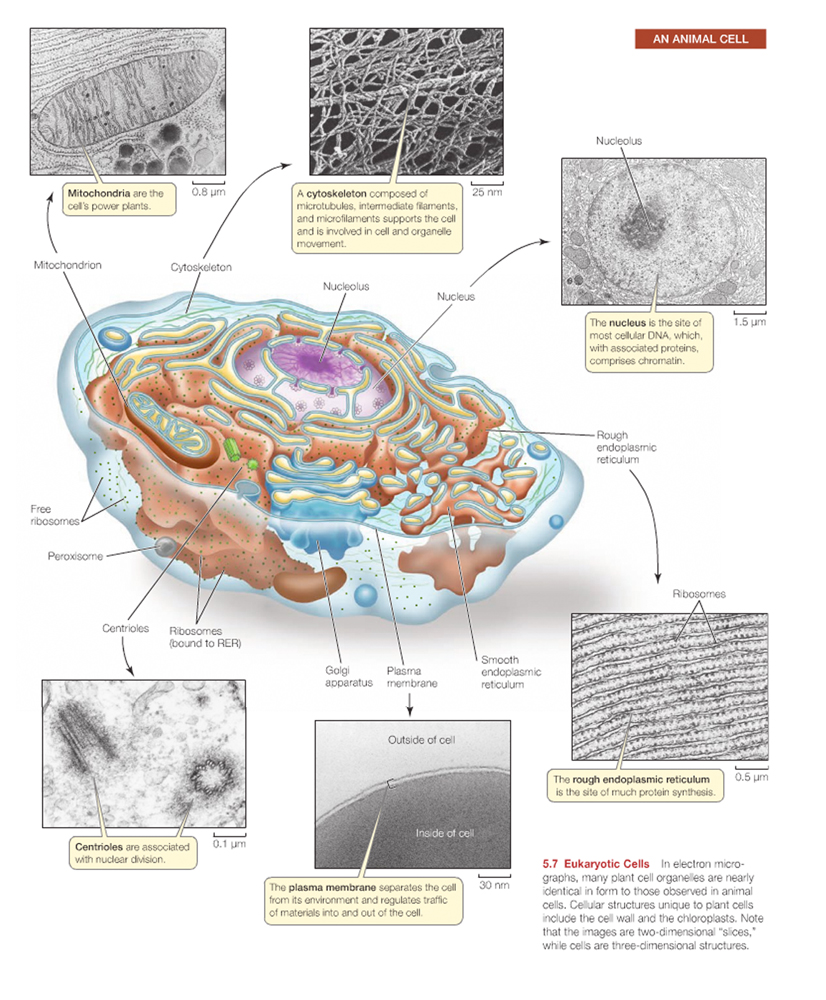

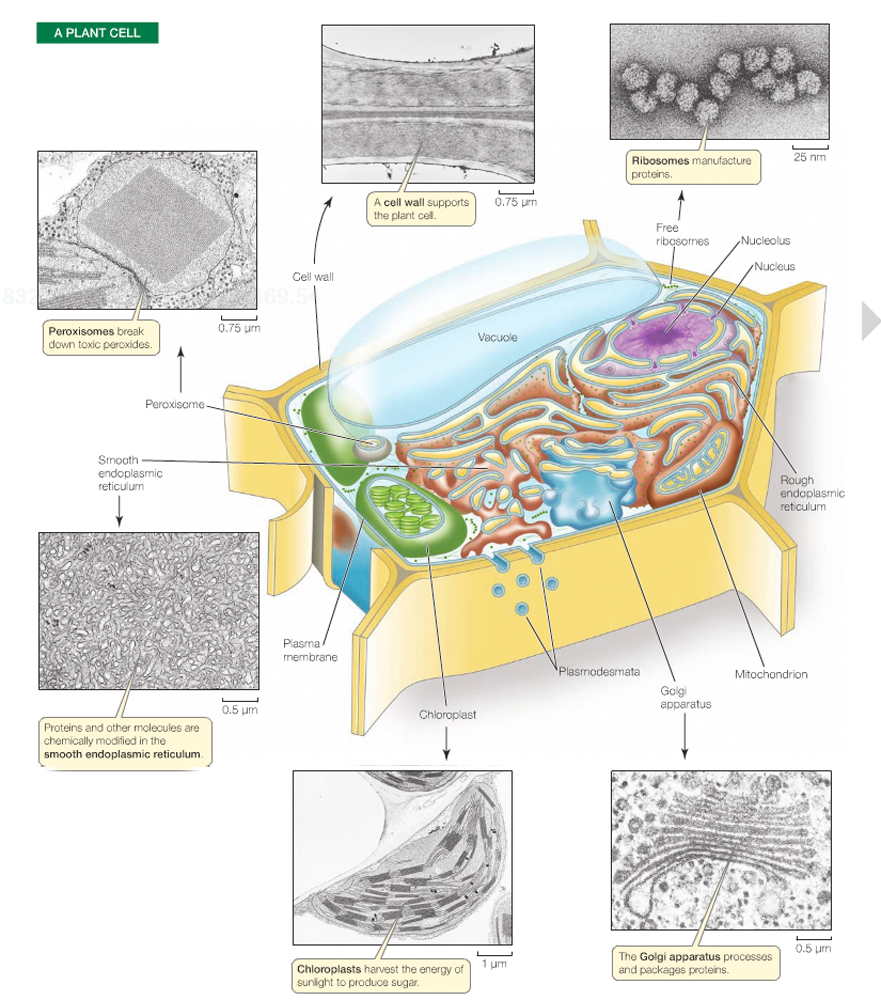

Essentially, Mendelian genetics is the genetics of the nucleus, but other cytoplasmic organelles can also carry genetic material.

Mitochondria, chloroplasts, and other plastids possess a small amount of DNA.

Humans have 20,000 - 25,000 genes in the nucleus, and 37 genes in their mitochondria.

Plastid genomes (succh as chloroplasts) in plants are five times larger than those of mitochondria.

Thus, any true definition of an organism's genome must include the total configuration of genetic material.

Note: Mitochondria and plastids are passed on by the mother only, as the egg contains abundant cytoplasm and organelles. The mitochondria in sperm do not take part in gamete union.

The hunt for the Mitochondrial Eve??

Are the two types of male and female specific evolutionary locations compatible?

There is a 4th non-Mendelian type of inheritance, this is known as "epigenetics" where modification of the proteins that wrap around the DNA -which gives rise to localized opening up or closing down of the Chromatin... These changes will allow or dissallow gene expression.

Having now fully understood (?) all the major types of variations from "normal" Mendedlian type genetic patterns of inheritance does our newly found insight into Mendelian genetics have any impact upon our appreciation of evolution?

Remember, while "....populations evolve and individuals do not", the gene pool of a population is the summation of all the individual genomes within that population.

To rephrase the question, therefore, How might an understanding of Mendelian genetics (which addresses phenotypic expression of an individual's genes) allow us to understand phenotypic/genetic changes within a population?

Genetic Variation within Populations

To recap (in light of the last few lectures):

For a population to evolve, its members must possess variation, which is the raw material on which "agents" or "forces" of evolution act (genetic variation within a gene pool).

We observe phenotypes in nature: i.e. the physical expressions of genes.

A heritable trait, however, is a genetic characteristic of an organism that is mainly influenced by the organism's genes (we cannot forget totally the influence of environment on this expression).

The genetic component that governs a given trait is called its genotype.

A population evolves when individuals with different genotypes survive or reproduce at different rates.Genes have different forms called alleles.

A single individual has only some of the alleles found in a population.

The sum of all the alleles in a population is its gene pool, which contains the variation (different alleles) that produce the differing phenotypes, upon which change can come about...evolution.

Most populations are genetically variable.

Natural populations possess inherent genetic variation.

The reproductive contribution of a genotype or phenotype to subsequent generations relative to the contribution of other genotypes or phenotypes in the same population is called fitness.

This "fitness" of any particular genotype is determined by the average rates of survival and reproduction of individuals within that population with that particular genotype;

i.e. the relative reproductuctive contribution of a given genotype.

For example, Man's highly selective preferences for certain edible crops have placed a a selective pressure on the crops that have been and are produced, giving rise to a seemingly wide variety ofimportant crop plants.

Artificial selection in laboratories that have analyzed genetic variation in assorted laboratory organisms, such as Drosophila melanogaster have also revealed genetic variation in these fruit flies.

In Ecological terms a locally interbreeding group within a geographic population is called a Mendelian population.

The relative proportions, or frequencies, of all alleles in this population are a measure of its population's genetic variation.

Population Geneticists can estimate such allele frequencies for any given locus by measuring the numbers of alleles in a sample of individuals from within a population.

Such measurements can be seen in terms of probability, which can range from 0 to 1, wherein the

Sum of all allele frequencies at any given gene at any given gene locus = 1.

Thus, the allelic frequency, can be expressed in probabilities for any given trait, which can be calculated by dividing the number of copies of that particular allele in a population by the sum of alleles in the population.

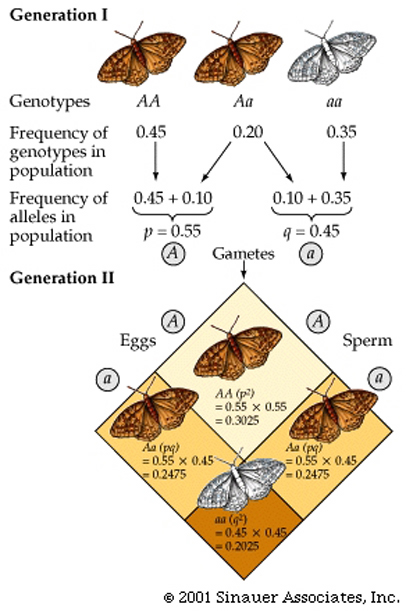

According to Mendelian genetics; If only two alleles (A and a) are present for a given locus, and both these alleles are found among the members of a diploid population, they may combine to form three different genotypes: AA, Aa, and aa.

Thus:

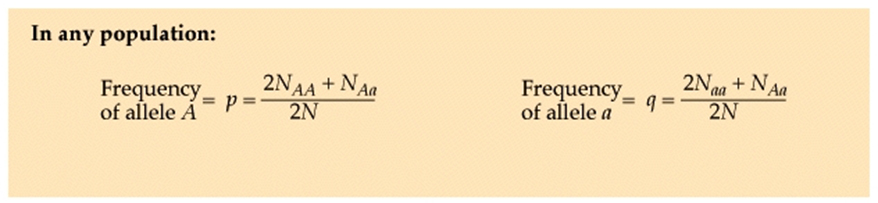

The Allelic frequency can be calculated using simple mathematics with the following variables:

n AA = the number of individuals that are homozygous for the A allele (AA). n Aa = the number of individuals that are heterozygous (Aa). n aa = the number of individuals that are homozygous for the a allele (aa).

Note that n AA + n Aa + n aa must always = N, the total number of individuals within the population.

Now let's look at it from the perspective of each alle at a given locus,

For the sake of discussion, let:

p = the frequency of allele A.

q = the frequency of allele a.therefore...

It is possible that the numbers of homozygous dominant and heterozygotes and homozygous recessives can change without changing the probability of finding individual alleles (p's and q's).

What about an example of how such equations can be used to calculate the frequencies of allele "A" and "a" within a population.

In essence, a population that is NOT changing genetically is said to be atHardy–Weinberg equilibrium; in that the allelic and genotypic frequencies within a population has reached this state and do not change from generation to generation.

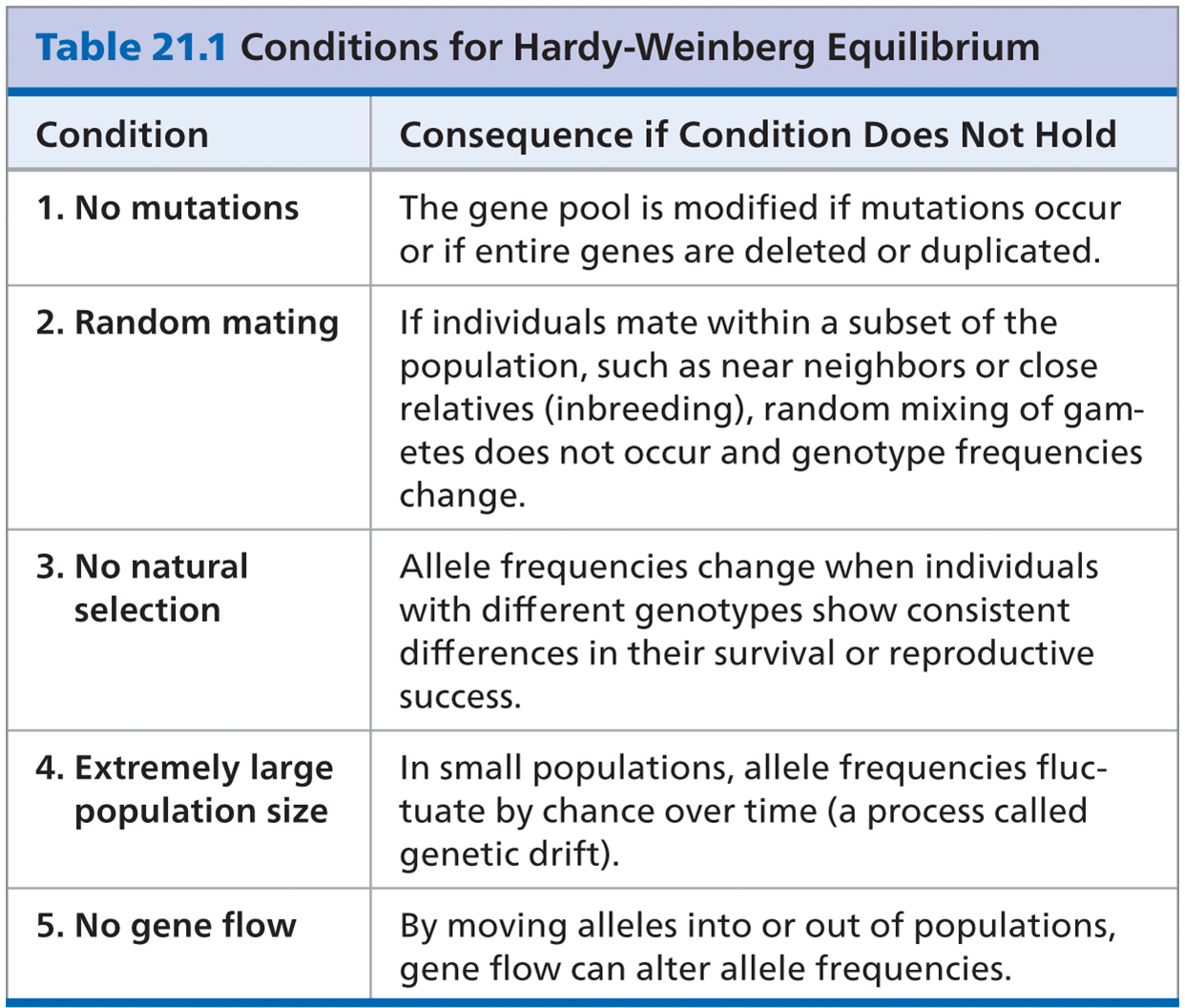

To appreciate the importance of the HW equilibrium, Five essential assumptions about the population must be made.

IF the above conditions of the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium are met, two consequences must follow.

(a) The frequencies of alleles at a given locus will remain constant from generation to generation.(b) After one generation of random mating, the genotypic frequencies will not change.

Restating the second result in the form of an equation that takes into account the allelic frequencies, produces the Hardy–Weinberg equation:

p2 + 2pq + q2 = 1 An example of the Hardy–Weinberg equation in use (see below), and how it is derived from Mendelian first principles can be seen below.

Note that this example also shows that there are two ways to produce a heterozygote, hence the overall probability for obtaining a heterozygote is "2pq", not just "pq".

So, why is this "Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium" so important?

Because it suggests that allelic frequencies remain the same from generation to generation unless some agent acts upon them to change them... and that something is EVOLUTION.

Thus, dominant alleles would not necessarily "dominate" the presence of the recessive allele unless either one had an effect upon any of the five criterea necessary to appreciate the HW equilibrium.

It also illustrates the distribution of genotypes that can be expected (for a given population) at "genetic equilibrium" for any value p or q (which can be determined empirically).

But the conditions for any maintenance of the equilibrium are far too stringent for any given natural population, so...

is it relevant to the real world?

Yes. It is the equivalent of a "null hypothesis" to the scientific method. ie it is the condition where "nothing happens".

As such, it allows scientists to determine (a) whether evolutionary agents are operating and (b) the identity of the agents that might be operating to change the pattern away from the equilibrium.... Erin Brokovitch story

Microevolution: Changes in the Genetic Structure of Populations

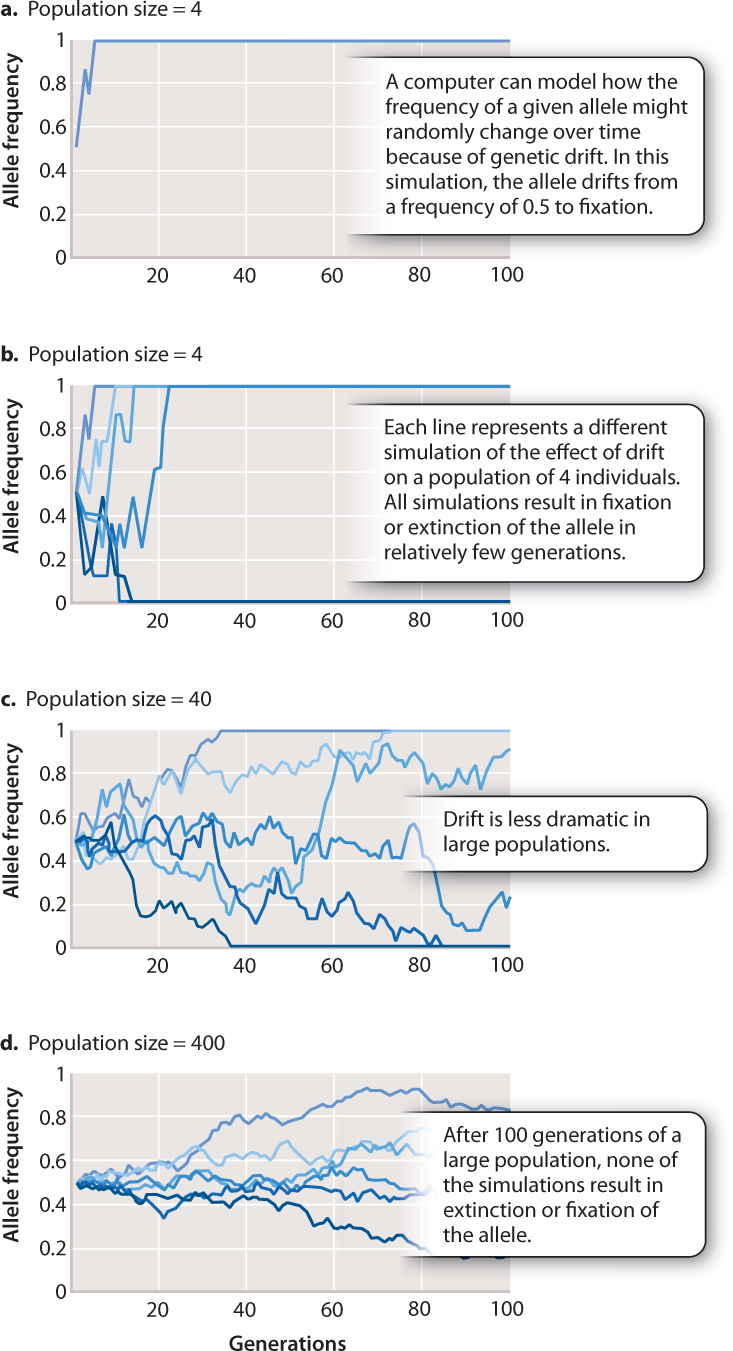

"Evolutionary agents" cause changes in the allelic and genotypic frequencies within a population.

Since the changes in the gene pool of a population constitute small-scale evolutionary changes, they are referred to as microevolution.We have discussed -to varying degrees- that some of the known evolutionary agents are gene flow, random genetic drift, non-random mating, and natural selection.

To a limited extent, we have also discussed, mutations, which are changes in the genetic material that can either be deleterious or beneficial to the function of an allele/gene, and which may or may not be selected for or against in a given population..

While most of these mutations appear to be random (e.g. copying errors, as the DNA is synthesized), and are normally either harmful or "neutral" (i.e. they do not affect their bearers ability to survive, and or procreate), some mutations are actually beneficial. Whatever the direct consequence they provide for a heterogenous population.

Indeed, the origin of all genetic variation is heterogeneity in the germ-line cells (why do we not care about somatic cell variations?)

Even though mutations are sufficient to create considerable genetic variation mutation rates, are relatively low; approximately one mutation per million loci is a typical frequency.

Thus, even though the very presence of mutations within a population means that one of the principle conditions that are necessary for the Hardy–Weinberg equlibrium to exist can never be met, the rate at which mutations arise at any particular locus is so low that the consequences of any neutral mutations would result in only very small deviations from Hardy–Weinberg expectations.

If large deviations are found within a population, then either the mutation is selective, or it would be appropriate to look for reasons why the mutation rate is so high -i.e. look for evidence of and additional agent that is causing the problem.

Such analyses have added important insights into how we can view evolutionary changes that have occurred over the ages, and have allowed us to appreciate that evolutionary rates can vary in two ways: slowly through "neutral" mutational changes to a gene pool and/or quite dramatically by some other changes in the assumptions that would normally hold for a gene pool in some form of equilibrium.

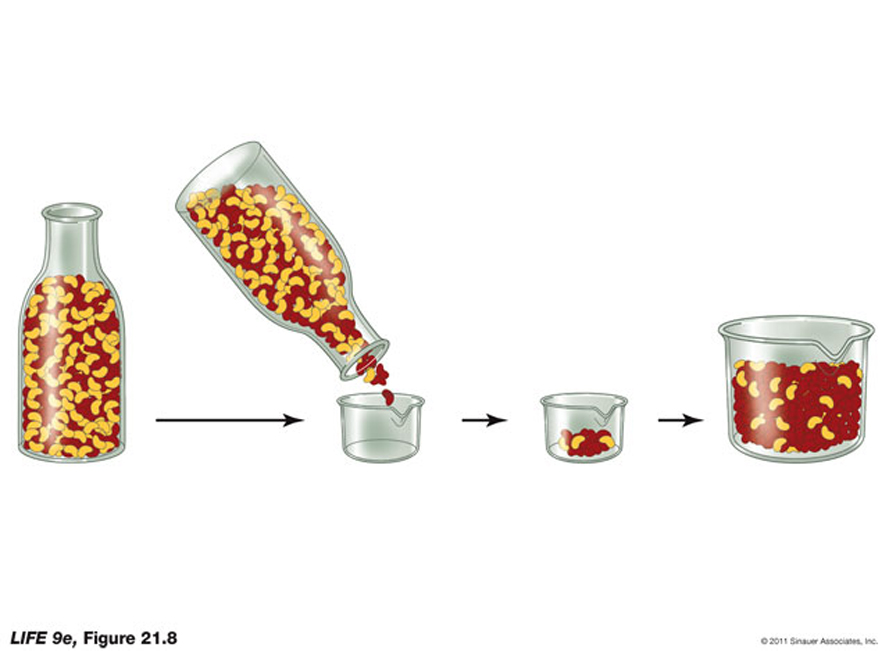

Hopefully helping to understand some of the different variables that have helped create evolutionary changes over evolutionary time and how the rates of change can differ for different types of living organisms. For example, it can detect potential "bottlenecks" in population development, as the ferquency of alleles, under this circumstance would be severely reduced.

About Contact GSU Academics Degrees & Majors |

Admissions Undergraduate Research Dept. of Biology |

Libraries University Library Campus Life Housing |

Athletics Alumni

|

|